- Home

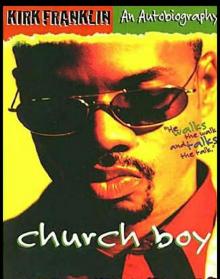

- Kirk Franklin

Church Boy Page 5

Church Boy Read online

Page 5

But the next day we started doing the quarter hours, and this time I didn’t have a clue. Man, they laughed at me! I’d give the wrong answer time after time, and Tanya was so embarrassed she said, “Kirk Franklin, you’re just stupid!” I mean, I went from hero to zero in two days’ time!

I bring that up because that’s how a lot of my childhood was. When I was playing the piano and making music I was the hero, but when I was doing anything else I was the clown. In my memory that seems to be the best image I can think of for my whole growing-up experience.

Gertrude’s husband, Jack, had relatives who lived down the street and around the corner from us. You would think it would have been nice to have family nearby, but that wasn’t really the case. Now remember, I was adopted, so I wasn’t really a Franklin, and all these cousins and kinfolk let me know it in no uncertain terms.

Their attitude was, “You’re not family, and you don’t belong here!”

I tried to act as if I didn’t care, but you know how those words hurt me. I always seemed to be on the outside looking in.

Jack’s sister had grandchildren who were about my age, and next door to them lived a bunch of cousins who were also about the same age. Across the street there were kids our age, and there were others who’d come over to play. There must have been fifteen or twenty kids in that group, but I was the one they all decided to laugh at and pick on.

I’m sorry to say, it wasn’t just the kids who gave me a hard time; even their parents joined in. I could come around the corner and the grownups would make their children go inside the house because they thought I was bad.

I wasn’t bad. I was just weird! I was just so excited about the idea of playing with other kids that most of the time I would overplay. It’s like the kids who get the ball and want to make every shot. I didn’t get to play with kids very often, and I was starved for it. So when I got to be with kids my age I just went crazy. But that made the other kids (and their parents) think I was some kind of weirdo. And maybe I was!

When Gertrude would go to keep house for the white family I mentioned earlier, she would usually take me along. She didn’t want me underfoot while she was working, though, so she’d drop me off at a recreational complex called the Bethlehem Center. It was like a YMCA, run by the city.

I was small and puny, and I’d been raised by an old woman, so I didn’t really fit in with most of that crowd, and I didn’t know how to play. Most of the boys were hard and tough. They knew how to fight, and they could spit and curse and do stuff like that. So whenever we would play football or basketball or soccer, I’d get killed. And whenever we played indoor games, they didn’t want anything to do with me because I was too little.

There was just one thing I could do that was outstanding, one thing that made me stand out in a good way. I could play the piano. People always liked me when they found out I could play the piano. The girls liked me, and they would hang around with me when they discovered I could play.

So, as you might imagine, it didn’t take me long to realize this could be a good thing, and I learned to take advantage of my talent. I’ll never forget one particular day, during recess, when I went into the room where the piano was and I started playing. I wasn’t showing off or trying to impress anybody at first. I just saw the piano and felt like playing.

Well, before I knew it, all the kids started coming in from all over the place. They said, “Oh, Kirk Franklin, you can really play the piano!”

Then somebody yelled, “Hey, Kirk, can you play ‘Stayin’ Alive’?”

So I started playing all the hot seventies songs. I was just playing along, laughing and having a great time, and it turned into this big party. Before it was over, I had turned the whole recreation center into a big concert. I’ll never forget that.

I was probably about seven years old at that time, and I had the place going wild. At last, a moment of glory! It was so refreshing not to be the butt of everybody’s jokes for a change. That day stands out as one of my fondest memories of those early years.

RAINY DAYS

By the time I got to the fourth grade, I was going through some major changes in my life. In one case, what should have been a blessing turned out to be a nightmare. Thanks to some crazy computer glitch, or maybe due to some teacher’s totally misguided recommendation, I accidentally wound up in the magnet-school program in Fort Worth.

If you’re not familiar with the magnet-school concept, then you should know that magnet schools are special schools for kids with special academic qualifications. Boys and girls are brought together from all over the community to participate in accelerated programs of various kinds. Magnet schools were really coming on strong back in the late seventies, and I think there are still quite a few of them around today.

So the city of Fort Worth had started a magnet-school program in our area, at Eastern Hills Elementary, and however it happened, I got a letter saying I had been accepted as a student in this new program.

Gertrude and I didn’t know what to think. It seemed like an honor, but there was absolutely no evidence in my record to suggest that I was that bright. I didn’t perform well academically. Besides, I hadn’t applied for admission and didn’t know anybody who might have recommended me, so it was strange.

As I said earlier, I was always doing something else, like day-dreaming, when the other kids were working on their lessons. Most of the time my head was in outer space or somewhere else, and I was either drawing or playing games or acting crazy, because my mind was so active and I thought school was so incredibly boring.

Despite our doubts and concerns, the school district decided I would have to go to this magnet-school program— and I absolutely hated it.

First of all, I hated moving from one school to another. I had to be bused to the new school, and that was no fun. But, as I suspected, it didn’t take them long to realize they had made some kind of technical error. I wasn’t supposed to be there!

Sometime during the second six weeks the principal called and asked Gertrude to come up to the school. We all got together with my teachers, and they said my grades weren’t up to the standards of the school. As far as I know I was the only kid this happened to, but I was sure it was some kind of computer mistake.

So there I was, at a school where I knew I didn’t belong. Rather than embarrass me, they decided to let me stay the rest of the year, but it was a strange time. I remember at one point we had to write limericks in English class. This was in the fourth grade, and the reason I remember it so vividly was because of the reaction of the teacher.

My limerick wasn’t like the others. It wasn’t funny like most of them. It said:

There once was a kid named Kirk;

The kids all called him a jerk.

When he went out to play,

It turned into a rainy day.

That goofy little kid named Kirk.

I realize now what a sad statement that was, but that was how I was feeling at the time. My teacher was surprised when I read my verse, and I don’t know whether she was angry or shocked. But she looked at me very strangely. Maybe she realized I was a sensitive child, or maybe she saw that I had a poetic nature. She probably just thought I was goofy!

Either way, I suspected that everybody in the class, including the teacher, knew I didn’t belong there, because I was always so far behind the rest of the class.

I was always challenged and embarrassed, and I felt the pressure more, I think, because I was the only black boy in the whole class. I don’t know why, but I always seemed to wind up in situations where I was the only little black boy in a sea of white faces.

With my grown-up eyes I can see now that there’s a hurting child inside the poem I wrote; but when I read it out loud that day, most of the kids just laughed at me. I didn’t think much about it until later, but I realize now what a cry for love it was.

Now, at Eastern Hills Elementary, the whole school wasn’t a magnet school. They had a magnet program, but they had regular class

es too. So, even though I was the only black kid in that particular class, there were black children in the regular classes.

And I remember that there was one particular teacher who made a real impression on me—Mrs. Barnett. She was the only black teacher I had any contact with at the school, and she was really on it! I thought she was the bomb! I mean, I was impressed with everything she did. She talked as well as any of the white teachers, she was smart, and she just sounded good. I was really glad she was there.

Mrs. Barnett helped me, and she gave me a chance to get involved. They had a black history program at this school, and she asked if I’d like to give the Martin Luther King speech that year.

Now, if you’ve heard it or read it, you know it’s a long speech, so I was reluctant to try it at first. But Mrs. Barnett encouraged me. She assured me I could do it, and she took her time with me to help me learn the words all the way through. On three or four occasions, she even took me home with her after school to give me extra time to practice. I’ll never forget that. She really focused me.

It’s fascinating when I think about it now, how that one teacher would take the time to do something special for a kid like me. I mean, there I was, knowing I was in the wrong school, with the wrong people, doing the wrong stuff, and this woman took time from her busy schedule for me—to encourage me, to teach me, and to help me do something I could be proud of. It was a blessing I’ll never forget.

I remember getting up in front of the whole school that day, and I really got into the part. I had seen Dr. King give that speech on TV when I watched the special about his assassination, so I knew what it was supposed to sound like. I went up to the microphone and recited the whole thing with as much expression as I could give it:

Even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up, live out the true meaning of its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.” I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave-owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood. I have a dream.

That’s just part of it, of course; I memorized the whole speech, and I still remember it to this day. My grandkids will probably have to listen to me recite it thirty years from now! They won’t be able to escape it!

Obviously, that experience made a big impression on me. It’s such an important speech, especially for African Americans and especially during black history week. I had been selected to stand up in front of the whole school to give this important address, and that was the one meaningful thing I got to do while I was at that school.

I had never wanted to be an actor, but I got to be one that day. I didn’t have to read the words, because I knew them by heart. And I tried to express the same passion and emotion that Dr. King had felt, standing there on the Capitol Mall in Washington, D.C. I said it just the way I had heard him say it. I felt those words in my soul.

I’m certain that the school district would have let me stay at the magnet school if my academics had come up, but of course they didn’t. So the next year, for the fifth grade, I had to go back to my old school.

MAKING SENSE OF IT ALL

What impact did that year have on me? Was it a good experience, being transferred back and forth like that? Did I gain from it? Yes. I would have to say I gained, even though it was painful for me, because I got a glimpse of a different world; and, for the first time, I saw how the other half lives. I’m glad I did.

The emotional stress I went through during all of that, however, reminds me of something I read recently that said the emotional pressures that turn some people into geniuses are the very same ones that drive other people nuts. Well, I can’t swear that’s true, but the idea sure makes sense to me!

When I think about some of the pressures I was living with when I was growing up, I’m amazed I ever survived. But I don’t have any bitterness about my childhood. I’m just glad I did survive, and I’m glad that somehow God used those things to make me stronger. I stumbled and fell more times than I can count. But I’m still standing, and I feel that I’ve been blessed in a very special way.

Someone told me not too long ago that being an outsider— being ridiculed and made fun of like I was—may have been the thing that drove me to express my musical talents as I have the past several years. They said that if I God had not allowed all those pressures and rejections, I might not have written the songs or had the blessings or Godly success I’ve enjoyed lately.

Even if that’s true, it doesn’t make the memories any easier or take away the sting of those old pains. We tend to think our experiences are unique when they happen, and we think that what we’re doing is just part of some natural evolution. We don’t think very much about the big picture.

But I’m pretty sure, in either case, that I would never volunteer to go back through those things again, even if I knew they might help me achieve some level of Godly success later in life. It’s definitely not worth it!

But even in the hardest of times, when I was ten and eleven years old, a lot of people were beginning to say that I was probably going to be involved in music when I grew up. By eleven years old, I was leading the church choir at Mount Rose Baptist Church, and in hindsight, I suppose that is pretty remarkable—though it didn’t seem very remarkable at the time.

There were two sides to that story too. On one hand, it wasn’t easy getting the older adults even to let an eleven-year-old kid tell them how to sing or what to sing. They complained loudly until somebody finally said, “Hey, you know, the kid’s pretty good!” I suppose that should have told me there was something going on—that maybe I did have a gift God could use—but I didn’t see that at the time.

As I think about it now, I can almost imagine God looking down at this little kid and saying, “Now, how in the world am I going to channel this strange little boy so he’ll wind up going with his heart instead of his emotions? How can I teach him to love and not to hate?”

He may have said, “One way I can do that is to give him a hard life so people won’t like him—so he’ll have to look a little deeper for the meaning of things—and so he’ll have to turn to Me for help and guidance.”

Is that just my imagination again? Maybe. But maybe not.

I would soon find out that there were times still ahead that would be even harder than what I had experienced up to that point. If I thought things had been tough in grade school, by the time I got to junior high school I found out I hadn’t seen anything yet. Now that was a challenge!

That’s when I met Marcus. For whatever reason, Marcus and I started hanging together, doing things, and for the first time I began to think that maybe I could have a friend in life. For the first time, I had me some homies who weren’t bashing me all the time and giving me a hard time about being “Church Boy.”

Marcus knew about stuff I only dreamed about, things like being a player, being liked by the girls, and being popular. I was so excited about going into junior high, I can still remember everything I was wearing the first day of school. But for all my expectations and optimism, it was a culture shock.

Except for that one disappointing semester at Eastern Hills magnet school, I had been in all-black schools all my life, so there was nothing about the culture I was going into that was new to me. But I had never seen anything like the older kids in junior high. I had never been in schools where the boys were so hard, so cool, and so together. At least, that’s how it seemed to my young eyes.

These kids were in the seventh and eighth grade, just one or two grades above me, but they were so far ahead of me in everything else that I was hypnotized by everything they did.

Then I met Marcus, and I sort of inherited a whole network of friends. Marcus not only had friends in the junior high, he had friends and uncles in the high school just down the street. He knew people, and he knew the gam

e. He was very popular, but for some unknown reason he and I hooked up. Suddenly I had some juice.

We would go up to the high school every day after school. We had to go up there to catch the city bus to go home. I felt like I was on another planet, but Marcus knew people at the high school and had seen things I didn’t know about. He knew how to be cool, and I was impressed with that.

But one day when Marcus was joking around with me he grabbed my jacket and threw it in some water. All the older guys were laughing at me, and once again I was just this little kid. I was surprised and hurt. I couldn’t say anything or do anything about it, so I just walked away crying. I thought that was the end of our friendship and that Marcus had just been making a joke of me all along.

But somehow he got my phone number, and later that night he called my house and apologized. He could see that I had been hurt by what happened, and after that he let me start hanging around with him and his friends. Now understand, Marcus and I were in the same grade, we were both sixth-graders, but he was way cooler than I could ever hope to be. He’d been around. He knew how to talk about sex. He knew all the curse words.

The next person who made a big impression on me at that time was a guy named Stacy. Stacy lived in our neighborhood, and I guess I should probably have met him before I met Marcus, because he lived closer. But Stacy lived across the tracks. My house was in a neighborhood called Riverside, and, believe it or not, the train tracks ran right down through the middle of town.

It’s like you hear about, like something out of an old movie. One side of the tracks was horrible, and the other side was better. I lived on the side that was better, and the reason was I lived in a neighborhood with a lot more older people. It wasn’t better from an economic standpoint necessarily, but people where I lived were older and more settled.

But all the cool guys hung out on the other side of the tracks. They were tough. They all knew how to drink and fight, and they smoked weed. Well, one night Stacy spent the night at my house, and he knew some guys, so we went out and got some weed. That was the sixth grade, remember, and I was only about eleven years old at the time. We smoked a joint, and it was my initiation into the big league.

Church Boy

Church Boy